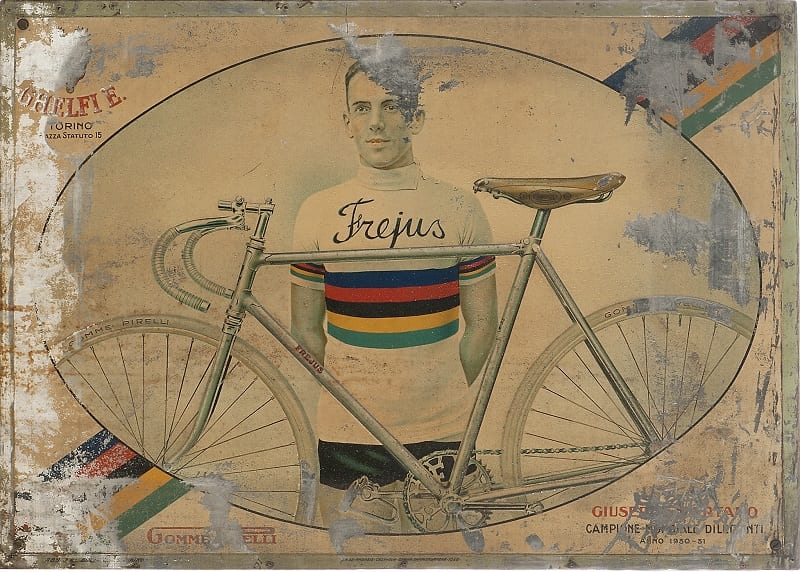

How was cycling developing at the beginning of the 20th Century? Let’s discover it with the documents of the Fisogni Museum archive

In the Fisogni Museum archive you can find an old booklet, which describes the bicycle with these words: “consider it like a woman to court, to care for, using really good manners”. Are you curious? Let’s start from the beginning!

The Italian Touring Club

It was 8th November 1894 when 57 Milanese cyclists decided to found the Italian Touring Club (TCI); its purpose was the diffusion of bikes, the newest means of transport: it was accessible to all and it allowed the development of a modern tourism.

Through a widespread system of representatives, hotels and accommodation facilities, TCI quickly diffused throughout Italy, involving also the rising field of cars.

This experience was not limited to Italy, and many Touring Clubs and other associations were founded in major European countries, each with its network of services, and TCI often signed agreements and conventions with them.

The Fisogni Museum preserves an important witness of Touring Clubs history: in its archive, in fact, you can find an old 1901 annal by TCI, with a glimpse of the diffusion of bicycles at the start of the last century.

Firstly, we must say that all data reported are closely linked to tourism; “We were told that tourism is a modern cavalry” we read “Of course, it has a big, a great advantage. While cavalry was restricted to the upper classes […] today cycling and tourism are for everyone”. So, in 1901, unlike in the past, the bicycle, similar to a modern steed, appeared as the way of the future, easily suitable and available to all. Not for nothing, in 1901 TCI had already 23.000 members.

What was the situation in the rest of Europe? The book gives us an answer: it reports in fact data and peculiarities of other European clubs; Europe was a continent very different from today, which was living its “Belle Epoque”, 13 years before the WW1.

Austria-Hungary, Belgium, North and East Europe

The first country in the book is Austria-Hungary: the Austrian Touring Club, we read, “seeks to a general development of tourism, particularly of a bicycle tourism, and to the spread of cycling in Austria”, both for “civil” and “military” purposes. Founded in 1897, the club had only 6.000 members, but it cooperated with the public administration to promote the growth of tourism and, as the TCI, it helped the development of road system, realizing first traffic signs.

There were also other societies in the Empire, like the Union of German Cyclists’ Societies (in Austria), the Magyar Society for “Velocipedists” (in Hungary) and the Czech Velocipede Union (in Bohemia, now Czech Republic). Each society had the purpose of “promote and encourage” the development of bicycle tourism. The Czech one had also a special attention to the competitive aspect.

The book describes also customs regulations; the Austrian Empire appeared quite flexible about cyclists’ transit: they only had to pay a tax of 25 florins, and then “the Cyclist can freely come and go” through the country.

The situation was similar in Belgium, homeland of Liège–Bastogne–Liège race since 1892; the local club had 18.000 members, while the Velocipede Belgian League focused on competition.

In Denmark, instead, they gave great attention to tourism, so there wasn’t “taxes on tourists’ velocipede”.

Similar organisations were present in Luxembourg (1.800 members), Netherlands (20.000) and even in Norway, which was a Swedish possession. In Sweden there was also one of the largest clubs, with 25.000 members, that wanted to promote the national territory in other countries. If the bicycle was imported for personal use, it was exempted from taxes.

The situation was far less developed in East Europe, under Ottoman rule. In Bulgaria and Rumelia there wasn’t a traffic regulation neither for bicycles, nor for cars; it was slightly better in independent Romania. The situation for tourists wasn’t easy also in the Kingdom of Greece: “The money deposited at customs is used for tips, so it’s very difficult to obtain a refund”.

In the hearth of the Ottoman Empire, the situation was quite disastrous: in Turkey there wasn’t any club or rule, and “apart from Constantinople, streets are impassable and not always safe”.

France and UK

French Touring Club (TCF), instead, was very large and well-organised, with its 72.000 members; it wanted to promote the use of bicycle, for civil and military purposes. Among the members there were “28 ministers, 178 ambassadors, senators and parliamentarians, 50 members of the State Council, 562 Generals and Superior Officers”. TCF was diffused also in the French colonial empire, and it worked together with the government to realise road signs, road maintenance, trips, projects. France also organized the first cycling race in history, in 1868, and the Tour the France would begin in 1903.

From a political point of view, TCI and TCF had concluded an agreement, which excluded Italian members from customs duties.

The English Touring Cycling Club was also well diffused, with 56.000 members, who wanted to “encourage and facilitate tourism – especially cycling travel”. It was “the oldest and the strongest federation” in Europe, founded in 1878. As the other clubs, the British one published many books and had an extensive network of agreements with hotels and other facilities. In the UK, home of liberalism, there weren’t customs duties.

Germany, Russia and other countries

The Touring Club of the German Empire was smaller (12.000 members) but highly active. It organised “touristic exhibitions […] and prizes to encourage the development of tourism and sport”.

The German Velocipede Union, instead, organised also “sportive meetings, races, games, tournaments”; the German Touring Club of Monaco was very important, too, with its 3.000 members.

Going in Germany, people had to pay 24 marks for every 100 kg, but if the vehicle was only for “private use” you could avoid the tax. In the Empire there wasn’t a clear road code, except for some big cities.

While in Switzerland the situation was well-defined, with a Club of 5.600 members, in Spain and Portugal there weren’t official organisations.

The last country to describe is the Russian Empire: in the Tsar’s land, the Touring Club had a difficult situation, because of “the restrictive provisions”, to the point that it had only 1.500 members, less than Luxembourg. The foreign tourists weren’t always well received, and they often had to wait for months to receive back his custom deposit. Some lands of the Empire, like Finland or Poland, had also other special rules. Anyway, the Russian situation was lively, and there were many organisations, as the Russian Cycling Union.

As you can see, the Fisogni Museum’s document reveals a mixed picture of Europe in these years, with solid situations in the “Great Powers”, like UK, France or Germany, while other countries were less developed. But there was also a common trend for cycling development, both for sport and military use; in a few years, the WW1 would be a tragic baptism of fire for bicycle.

Marco Mocchetti

Tags:

- bicicletta

- ciclismo

- impero ottomano

- impero russo

- impero tedesco

- touring club

- velocipede

- Prima Guerra Mondiale

- impero austriaco

- bell’epoque

- tci